Waiting for the light and getting your expose spot on is key for low light landscape photography. I often think that landscape photographers would be good at fly-fishing. Just look at the similarities. Both activities require a willingness to purchase expensive equipment. There’s often a need to be knee-deep in water.

Oh, and did I mention the one that got away? (Delete as applicable: a potentially award-winning fish/ sunrise or sunset that was oh so very nearly spectacular but didn’t quite come good).

The first attempt. I liked the composition, but not the lack of colour.

The strongest link is probably patience. Neither pursuit is ideal for those who want things to happen right here, right now. Both activities require an acceptance that in order to win the prize you often need to wait around.

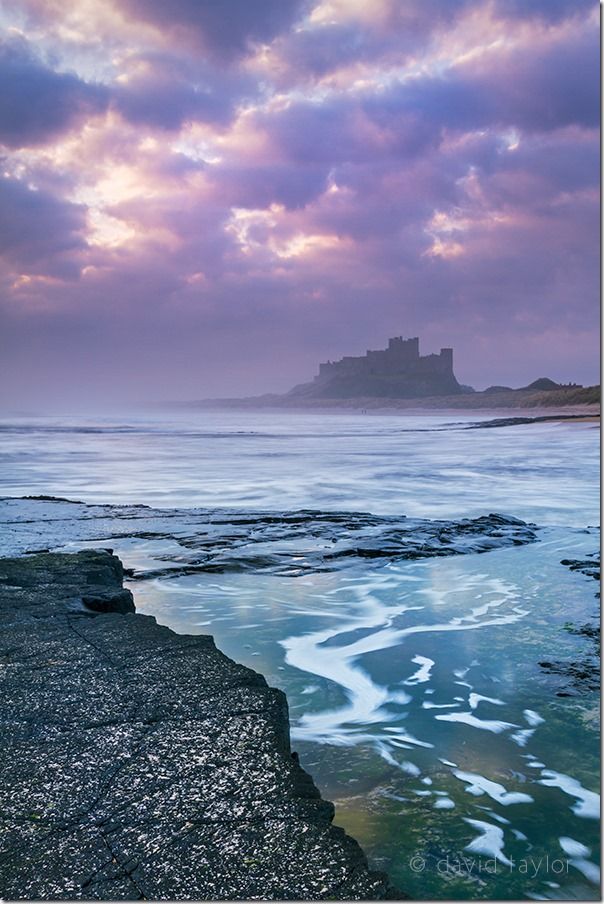

Which brings me neatly to this shot. It’s Bamburgh Castle on the Northumberland coast. It’s a spring morning and I’m knee-deep in water.

I’ve been at Bamburgh for an hour already. In that time I’ve shot a few images and well, they’re okay, but they’re not quite what I was hoping for. Bamburgh is a popular spot with photographers and in the past hour I’ve shared the beach with two others.

They’ve now gone. It doesn’t look as though there’s going to be any colour in the sky this morning so I don’t blame them. I’m thinking about packing up too. I’ve got to go to a meeting later that day so I need to get home and change.

Further up the beach I tried a horizontal shot. It was then that I saw the clouds starting to break up. Would I be in luck?

Just as I’m thinking these thoughts the cloud starts to break up. Joy of joy, colour gradually washes across the sky. This is the fish I’ve been waiting to catch. Fortunately, I’m prepared. I have a composition in mind. All I have to do is meter, check that I’m using the right strength ND graduate, and then press the shutter button.

However, there’s another factor to consider: the tide. The rock pool I’m standing in regularly fills and drains as waves rush in and recede. I’d like to capture this movement somehow. This means selecting an appropriate shutter speed.

I’m using an aperture of f/14. The light levels dictate a shutter speed of 2.5 seconds at ISO100. I could opt for a faster shutter speed but that would mean increasing the ISO or using a larger aperture. Neither are options I want to consider. So, 2.5 seconds it is.

The final shot. I returned roughly to where I started and waited for the right conditions to make the image.

When a camera is on a tripod there’s no point in pressing the shutter button by hand: this can introduce camera shake, negating the use of the tripod. Usually I’m happy to use the self-timer. However, this morning I need to fire the shutter at a very precise moment in time (a decisive moment in fact). For that reason I need to fit my remote release.

Once that’s done I’m ready. All I have to do is wait for the right wave. Oddly enough it’s easier to make the sort image I’m after as a wave recedes. It’s then possible to see how the water flows and what it will look like in the final shot. A breaking wave is less predictable, making it harder to pre-visualise the composition.

It’s then that my perfect wave breaks. A trickle of foam runs back along the rock pool as the water recedes. I have my photo of the morning. Now all I had to do was get home, process the image and get it printed out. How big? Stretch your arms out to their widest extent. That big. Actually no, bigger than that. Honestly. Would I lie to you?

If you would like to learn more about Low Light Photography or Fine Art Landscape Photography why not consider taking one of MyPhotoSchool’s 4 week online photography courses