It hits our rural and urban landscape, following the effects of Dutch elm disease, sudden oak death, and horse chestnut bleeding canker and the diseases of prunus and robinia that have limited their use as garden trees. It is therefore hardly surprising that the media are suggesting that Ash Die back could change the British Landscape in the way that Dutch elm disease did over forty years ago.

On the other hand the news may be received differently according to one’s relationship with the ash tree. Ash grows quickly and reaches statuesque proportions, often bigger than intended. Self sown seedlings and saplings can be a major nuisance, and ash is often referred to as a weed tree. Saplings that grow out of control may then become protected, causing problems for gardeners and home owners. It not therefore surprising that many raised their hands in horror at the thought of ash trees being imported from Europe. So why are they? What’s the attraction of this tree? Why is this disease so important? Is this another Dutch elm disease?

Whenever a story of this type hits the news some reporting can be misinterpreted or misunderstood. For example a spokesman from the National Trust appeared on National television underlining the gravitas of the situation by stating “some of these ash trees are over 1,000 years old”. The natural lifespan of ash is around 200 years. Ash, Fraxinus excelsior, grows quickly to 25 metres (75ft) but can attain 45m (140 ft). Trees are over 30 years old before they produce female flowers and therefore seeds, these flowers open before the leaves. Many of the ash trees are planted as urban landscape trees are selected clones that do not produce seeds, for example Fraxinus excelsior ‘Westhof’s Glory’. Ash is used as a landscape tree because it has a straight trunk and a high, light canopy that casts only light shade allowing grass and other plants to grow beneath. It grows quickly, and tolerates wind, pollution and salt-laden air. The leaflets are small, so do not block drains and gutters or smother grass, and they rot quickly after falling.

In urban locations the narrow leaved ash is often grown. It is more slender in habit with narrower leaves that colour beautifully in autumn. Fraxinus angustifolia ‘Raywood’ is the most popular form. Its main disadvantage is that the wood can be brittle, and branches are easily broken by wind in exposed situations.

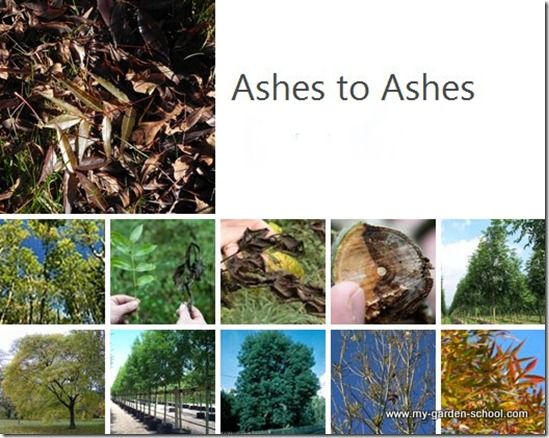

Ash die back manifests itself as black blotches on the leaves, often at the base of the leaf and midrib. The leaves then wilt. It is therefore unfortunate that the main focus on identifying the scale of the problem has been from late summer when the leaves are falling. Lesions also appear on the bark of stems and branches. These spread to destroy the bark and young trees can die in a season. More mature specimens succumb after a few years. It is worth pointing out at this stage that there is no known chemical or biological control, so control has to be through isolation, destroying infected trees and damage limitation. It is also worth noting that not all trees succumb, some appear to be resistant to the disease.

There is some conflicting opinion as to how the disease spreads. Reports say that the spores are unlikely to be spread by birds, animals and man. Despite this the media have featured recommendations that visitors to woods in infected areas should wash after their visit. In fact the recommendation is to wash the mud off shoes and bicycle tyres. This is probably sound advice as it seems that spores are active in leaf litter; they are produced from infected dead leaves during the summer months.

But could the disease have been wind borne from Europe, especially as most identified cases are on the eastern side of the country? Is this likely for the disease to be windborne for long distances? The Forestry Commission website states that trees need a high dose of spores to be infected, and that the spores are unlikely to survive for more than a few days. Infection from windborne spores from overseas seems even more improbable.

The Royal Horticultural Society’s website states that “the main pathway of spread over long distances is through the movement of diseased ash plants and logs and unsawn wood from infected trees”. High volumes of the common ash are imported very year for forestry and landscape use. Despite the prevalence of the disease in Europe during the past 20 years has this been regulated? Is imported stock subject to the inspection necessary for control?

The disease was first confirmed in the UK this autumn, it is still recent news. As at 8th November 2012, according to the Forestry Commission the disease had been confirmed on 15 nursery sites, 55 recently planted sites and 65 sites in the “wider environment”, in other words established woodland. Does this suggest that the disease is more prevalent in newly planted, possibly imported ash trees? Could it have spread from here into native populations?

Some British Nurseries do grow their own ash trees using British grown understocks of Fraxinus excelsior; they then do their own budding of clonal selections, and grow them on in the open ground or containers. These can be more expensive than imported trees, but the cost compared to the other elements of any size development project are minimal. British nurseries with stocks of home grown elm anxiously await the outcome of current restrictions on movement and sales. The financial implications for responsible British tree nurseries are substantial. The question remains as to whether landscape architects and designers will specify ash in the future. If not, what’s the alternative?

Will Ash die back change the face of the British landscape in the same way as Dutch elm disease? No-one really knows. One thing is certain the disease has done little for the popularity of a tree of mixed reputation that plays a more important part in our lives than we sometimes realise. Could it have been prevented?