Where and when the sun rises and sets: Solstice and Equinox

In a few weeks’ time we’ll reach a date that few celebrate, but one that’s important to landscape photographers: the summer solstice. On the 21st June the hours of daylight will be at their maximum in the northern hemisphere and at their minimum in the southern. From then on the nights will slowly lengthen north of the equator and shorten in the south.

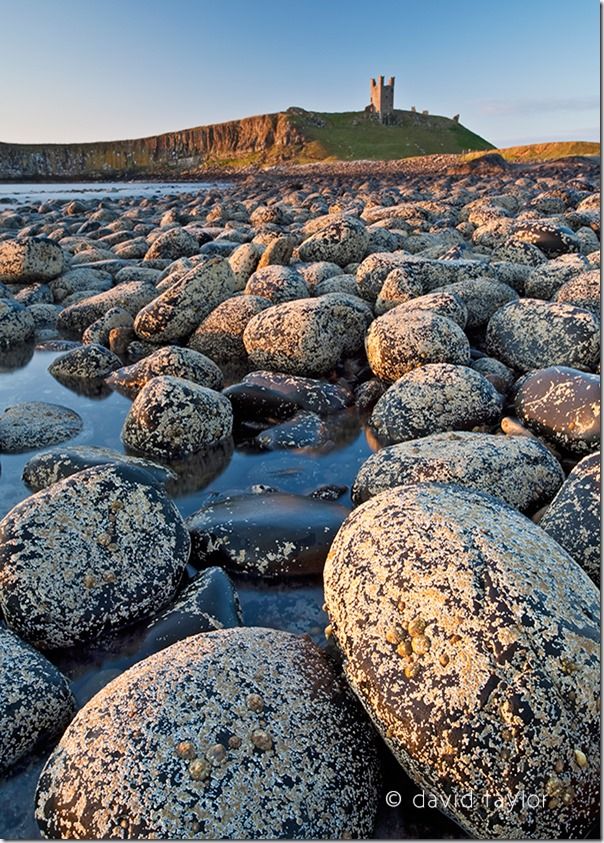

This was shot at dawn at the time of the spring equinox. At the summer solstice the sun will rise further north, lighting the sea stack from the left.

On 21st September we come to another significant event: the autumn equinox. The word literally means equal night. On this date night and day are exactly the same length everywhere on the planet (for some reason I find that strangely reassuring). Three months after that is the winter equinox.

On 21st December the daylight hours are at their shortest in the northern hemisphere and at their longest in the south (the exact reverse of the summer equinox). Finally, on the 21st March we come to the spring equinox and equal day-night, with the cycle beginning again when we reach the summer solstice once more.

If you stop to think about it this is all very odd. Why should the length of night and day very so much? In a more rational universe you’d expect a permanent state of equinox.

This view of a north-facing cliff on the Northumberland coast is only lit at sunrise during the summer months.

We have this variability because the Earth is tilted at 23° relative to its orbit around the sun. On 21st June the North Pole is tilted towards the sun. If you live in the Arctic Circle this means you’ll never see the sun set for days, even weeks around the date of the summer solstice.

However, live in the Antarctic and you’ll experience Polar Night, permanent darkness for weeks on end. At the winter solstice it’s the South Pole that’s tilted towards the sun and it’s the north that suddenly finds it harder to get up in the morning.

Another effect of the Earth’s tilt is that the direction the sun rises and sets changes over the course of the year. At the summer solstice (and at a latitude of 50° north and south - approximately the latitude of London and Punta Arenas respectively) the sun rises roughly in the northeast and sets in the northwest.

At the winter solstice the sun rises in the southeast and sets in the southwest at the same latitude. It’s only at the equinoxes that the sun rises almost directly due east and sets due west (the equatorial regions see the least variation during the year, the further north and south you venture the greater the variability).

Near the Arctic Circle there is a permanent state of twilight during the day during the winter months. The sun never rises above the horizon so it never gets entirely light.

For photographers this variation makes a big difference. You first need to known when the sun rises and sets. You don’t want to arrive at a location far too early or, even worse, too late. There are also some subjects that work better at one particular time of the year than another.

North-facing subjects may better served by shooting during the summer months for example. Fortunately, there are many tools to help us photographers make informed decisions.

The most useful online tool I’ve found for calculating sunrise and sunset times and direction is http://suncalc.net. There are also many Smartphone apps that do a similar, and more mobile, job. Another advantage to using a Smartphone is that you can set the alarm to wake you up when required. I don’t know about you but that’s a far more necessary facility in the dark winter months than in sunny June.

If you would like to learn more about landscape photography why not consider taking Sue Bishop’s 4 week online photography course on Fine Art landscape photography.