Those of us who are passionate about gardens and gardening tune into programmes on the TV and radio, we go online and discuss our successes and failures and post questions for advice in various fora. And at weekends we descend on garden centres or make pilgrimages to out-of-the-way specialist nurseries in order to purchase new plants. Because that’s where plants come from, right? WRONG!

By far the greatest majority of our familiar garden plants (and the ancestors of modern hybrids) were brought to Europe over the past 400 years from then-unexplored parts of the world. In particularly, China and Japan, India and the Himalaya, Australia and New Zealand, and the Americas.

And even if the fact that most garden plants are émigré does ring a bell, how many of us are know about the forgotten heroes of horticulture who over the past 400 years risked their lives in some of the world's most remote and inhospitable regions to satisfy the public's thirst for ever more exotic and different flowers, shrubs and trees?

This introduction of literally tens of thousands of new, exotic, exciting and expensive species - both hardy of the garden and tender for the conservatory, was undertaken by the plant hunters.

During their work seeking out new plants in the remotest corners of the world this band of of brave adventure-botanists had adventures that read like something from the pages of Boy’s Own. And while the plant hunters did not grow rich on their finds, ‘their’ plants revolutionised garden styles and fashions. Herewith a few brief examples of the many adventures and dangers encountered by plant hunters and the results of their work.

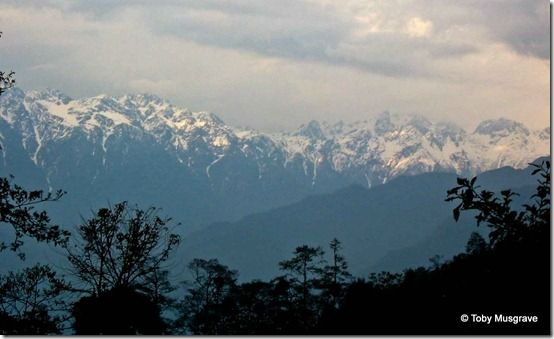

Sir Joseph Hooker (1817-1911), later the second Director of RBG, Kew was in 1847, the first westerner to enter Sikkim, then remote kingdom in the north western Himalaya. Hooker spent four years collecting and his greatest discovery was 28 new brightly coloured species of Rhododendron, the parents of the Hardy Hybrids. Rhododendromania swept Britain and between 1851 and 1871 it was estimated the same sum had been spent on rhododendrons as was then the national debt! The figure may be somewhat of an exaggeration for it then stood at about £800 million (£59,700 million at 2010 values). One of Hooker’s great inspirations was David Douglas (1799-1834) who explored California and the Pacific northwest in the late 1820s and early 1830s. He introduced nearly 200 new conifers to our landscape (including of course, the Douglas fir) which fuelled the fashions for the pinetum and arboretum (and established many timber industries globally) but the man himself was gored to death by a bull.

George Forrest (1873-1932) made seven expeditions to Western China (mainly Yunnan) between 1903 and ’32, during which time he found over 300 Rhododendron species. An achievement that required the whole genus be reclassified. In 1903 only he and one other of his team of 17 survived an attack by murderous lamas (monks). Forrest was hunted and survived nine days without food, walking barefoot (imprints from his boot soles would have been a giveaway) and once evading his pursuers by hiding in a river breathing through a straw. The thousands of hardy species he introduced did much to shape Edwardian Arts and Crafts and inter-war suburban gardens.

© Text Toby Musgrave. 05 October 2012